Most young people have a dream or two—that is, visions of what they want to make of their lives. Ideally, they come up with plans to pursue them. Can they earn a living while pursuing those dreams? If not, how will they support themselves? What do they need to get out of their education?

Of course, even the best plans are subject to the shifts and uncertainties of the world. We must constantly revise our plans—and even our dreams—based on the feedback we’re receiving. But revising a youthful dream doesn’t mean giving up. Sometimes it can mean landing you in a pretty cool place.

This is what I discovered had happened to a college friend of mine. I got a call from him a few years back after not having talked to him in over a decade. As it happened, he had heard that I was in Washington, DC; he happened to be coming to the area for a fountain pen show and wondered if I would like to meet up. I expressed curiosity as to why he was coming all the way from the Midwest to buy a fountain pen. Well, as it turns out, my friend wasn’t looking to buy a pen. He was coming to sell the ones he was making by hand.

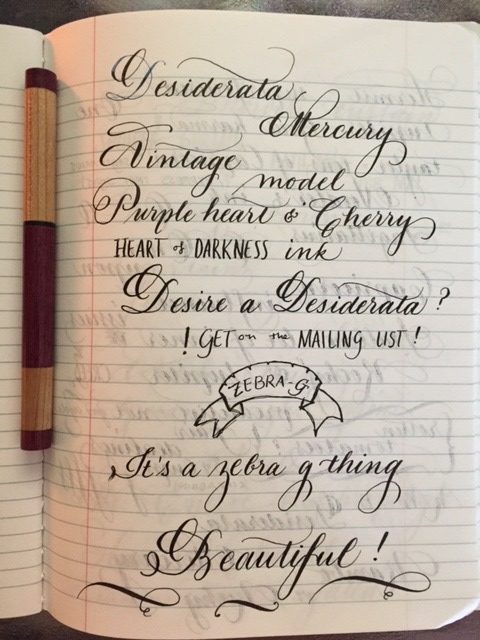

In 2013, Pierre Miller founded the Desiderata Pen Company, a one-man operation dedicated to producing affordable, handmade fountain pens. Desiderata Pens came into being after Pierre, a chemistry and music major, went looking for a fountain pen that met his needs at a price point he could afford—and found none. So he used the technical skills he’d been developing since he was a kid to design the pen he needed on his own. Now Pierre makes all of Desiderata’s pens by hand, crafting them in small batches and traveling around the world selling them. (He has quite a fan base in Singapore.)

What interested me most—and what I thought would interest you Third Factor readers—was the story of the path that a science major at Midwestern liberal arts school followed, not into a traditional job in a lab or engineering or any of those jobs you might envision when you think “STEM,” but to artisanship: designing, creating, and marketing something he wanted to exist in this world. And he has managed to pay his bills while doing it.

So I sat down to chat with him about the path he followed from childhood visions to successful artisan and entrepreneur.

Looking to Realize a Childhood Dream—While Earning a Living

“When I was a kid, I wanted to be a scientist because I thought scientists looked smart, and I wanted to be smart,” Pierre told me. He had some great science teachers, whom he credited with helping him find opportunities to try out this path. First came model rocketry; this led in turn to scale model building; which then led to woodworking and machine tools—skills that would one day prove essential to creating the perfect fountain pen.

But that wasn’t part of his vision back then. In fact, his dreams at the time weren’t centered only on the sciences: Pierre also had a love of the arts and humanities, including interests in music performance and writing. “I always liked writing short stories,” he explained. “And I always liked a good writing instrument.” He still remembers his first set of quality Paper Mate ballpoint pens. “Those were the first pens I had that mattered. I got a box of them on the first day of class from a generous teacher, and one at a time, I would write them dry.” After the entire box eventually dried up, in his freshman year in college, he knew he couldn’t go back to mediocre pens. So he got his first fountain pen: a Pilot Varsity, an inexpensive entry-level pen. Eventually, however, he discovered that the ink was not water-resistant (by being caught in the rain) so he switched over to the Pilot G2.

Of course, lots of people like pens. I myself have a fondness for the UniBall Signo (I found it while living in Japan, which is an excellent place to find quality pens). How, I wondered, did Pierre’s interest in pens, unlike mine, turn into a vocation? After all, he didn’t set out specifically to become a pen designer or even an entrepreneur.

Pierre’s goal was simple: find a job that paid. This may seem obvious, but it wasn’t something that came up much during his education. “At school, we talk about school; we don’t really talk about work,” he explained. “I was very interested in getting work, so when I did get information about work, I hung on to it.”

One such bit of intel came from a physics teacher, who informed him that it’s tough to find scientific work if you have a master’s degree but not a doctorate. “Businesses like to hire people with bachelors’ degrees as lab techs, grunt workers to be used by the PhDs, who do the ‘big picture thinking’ and then send you out to do the hard work,” Pierre explained. “But master’s students, they don’t really know what to do with. You’re too educated to be a grunt, but not ready to call the shots.”

Pierre knew he didn’t want to pursue a doctorate. He’d seen too many other people living with crippling amounts of debt, spending their twenties working intensely on something with no guarantee of a job. He also knew he wasn’t interested in working in academia. Adding that to what he’d heard about the employment prospects for scientists with master’s degrees, he decided to see where a bachelor’s degree in natural science would take him.

“I wanted to see if I had any success earning a living on my own, with what I had,” he said. “I wanted to hurry up and start making my own money and living my life.”

I wanted to see if I had any success earning a living on my own, with what I had. I wanted to hurry up and start making my own money and living my life.

Pierre Miller

The Post-Graduation Job Hunt

Pierre graduated from Kalamazoo College in 2005 and got his first gig as a lab technician in 2006. It was a contract job—which seemed to be all that was open to him as a bachelor’s level chemist. “So I bounced from one contract job to the next, making fairly good money, but always with the risk of losing the contract for no reason,” he recalled. “I really just hated trying to deal with that kind of a world. I think anybody would.” He also taught piano lessons in people’s homes through a company that connected him to students in exchange for a finder’s fee, which allowed him to pad his savings and get through the times between contracts.

Then, in 2008, he got the opportunity to intern at one of his favorite radio stations. “I thought, maybe it’s time to try something else,” he said. Accepting the internship meant he had to leave his job as a lab tech. Fortunately, just as his contract employers offered him no stability, he was not required to offer any to them.

“It was one of the most satisfying moments of my life when I got to call up my contract agency and say ‘You remember that clause that says that either of the parties can terminate the contract for any or no reason? Yeah….’” Pierre said. “I can’t tell you how satisfying that felt.”

After the internship ended in 2009—at the height of the financial crisis—with no possibility of a position, Pierre began a period during which teaching piano was his only source of income. It was during this time that he happened to watch a YouTube video that changed the course of his career. “Sometime around 2011 or ‘12, I saw a video by a fountain pen reviewer who was pretty famous in the fountain pen world who did a review saying there was a company that made water proof fountain pen ink—and it came with a free pen!”

Pierre got himself the pen, marking the first step in the path he is now on. First, he wanted to improve his handwriting to live up to what the pen offered. Then he realized that to really improve his handwriting, he’d need a model on which to base his improvement. This presented a difficult problem: the handwriting models that he was interested in assimilating all required writing instruments that were not commonly available. The closest fits were particularly old—so called “vintage” pens from yesteryear. With some luck, vintage pens could be found on eBay, but they generally needed repairs; if not, they were exorbitantly expensive. “I was doing nothing but teaching piano in Chicago at that time. For what I was doing, I was being paid well and I managed to pull it off, but there wasn’t a lot of spare money.

“So I thought, maybe I could repair the pens that didn’t work out and resell them,” Pierre continued. “After about a year and a half, I repaired about fifty percent of the pens that didn’t suit me and resold them. It was enough to keep the game going on, until eventually I found the perfect pen.”

Unfortunately, he could only find the one, and that drove home the inescapable fact that pens like this were rare, and if the one he found were ever to be damaged, it was game over. The secret to that perfect pen, was in the nib. “There existed a modern version of a type of writing point—which you can buy—that is reusable, inexpensive, and works, but wears out—because it’s regular steel, not stainless,” he explained. “I wanted to be able to use one of those nibs because it would allow me to do what I wanted, but there wasn’t a good option for buying a pen that used that nib. So after all this trouble, I thought, maybe I could reverse engineer something that would meet this need.”

Eventually, Pierre came up with some prototypes that, as he put it, “were decent and looked kinda like pens.” As it happened, one of his piano students happened to be an experienced tool and die maker; he showed Pierre the tools he would need to make his pens—what to buy, how to operate them safely, how to troubleshoot, and so on. “He got me started on the process of making these things. The plan was to sell them—but first I had to know how to make them.”

The Key Challenge for Artisan Entrepreneurs

When the Desiderata Pen Company came to that pen show here in the DC area a few years back, I had the opportunity to check out Pierre’s handiwork in person. My now-husband, a soon-to-be-published novelist, came with me; he was so impressed with the pens that he now owns two of them and uses them to write his novels by hand. So we can attest to the fact that he has successfully learned not only how to make pens, but how to market them as well.

Indeed, the need for a broad range of skills is the key challenge that an aspiring artisan must overcome. “It’s rare to find any person who has all the things that they need to succeed in a business all in one package,” Pierre said. “Everyone’s got some strengths and some weaknesses, and the business is not sympathetic to any of the weaknesses that you have. I struggle with a lot of things.” He told me about a friend’s father, self-employed in an industrial field, who asked him about the biggest hurdle he was facing with his fledgling company. “I said, me? I don’t work hard enough; I get distracted easily; pretty much everything thats wrong with my business is what’s wrong with me—one of my own personal failings.

“There was a person I met at pen show once who said, ‘Your business can’t be any better than your weakest employee,’” Pierre continued. “That’s what I would say. Who you are, what you can do—either adjust for it and improve, or just accept who you are what may come of it.”

Dream 2.0: Realizing What You Really Want

“I pieced together this idea that it’s important to think about one’s life and decide what you should be doing—what you want, if you’re content. What does it mean to live a good life?” As it happens, between graduating and getting his first lab job, Pierre spent a year teaching English in France. This experience afforded him a lot of time to be on his own and to think about precisely this question. And this, he said, was both essential and a luxury. “I don’t think a lot of people get the chance to have a lot of empty space in which they can do any kind of contemplation,” he said.

I pieced together this idea that it’s important to think about one’s life and decide what you should be doing—what you want, if you’re content. What does it mean to live a good life?

Pierre Miller

Before he got his laboratory job, he explained, he was consumed with the job search, just like all but the most fortunate recent college graduates. After he got that first job, however, he found he was constantly asking himself what he truly wanted to be doing.

“What I really wanted was a career as a concert pianist,” he said. “The career in chemistry was the means to taking such risks—to making such a career come to life.” But when he got the job, he faced a new problem: making the dream come to life in his spare time. “Because when you spend one third of your day doing a job that pays for the second third, you need to find time to practice. Practicing is one thing, playing is another thing. And promoting yourself and career development—that’s another thing! And at some point you’ve got to eat. I wondered, can this even work out? So then I asked myself, what do I even want out of a career as a concert pianist? If I had the job working in a tech field, it’s hard to even say what would have happened.”

In Search of Genuine Conversation

That’s the story of Pierre’s journey to artisanship in a nutshell. But our conversation didn’t end there, because just as he revisited and revised his vision for his career, he’s similarly revised his guiding vision for community and friendship.

Pierre was in a gifted program as a kid; now, as an adult, he knew he wanted to find interesting people who might make good friends. So he attended a few meetings of his local Mensa chapter.

“I don’t want to say that I had a bad experience, but I didn’t have anything close to the experience that I hoped,” Pierre explained. “I didn’t have much in the way of interesting conversations with people. I tried to reach out to others, but the things that I valued weren’t really being represented there any better than they were in the general population.”

“There are so few times that I’ve ever found myself wishing that I was more intelligent, compared to wishing that I were more wise or more patient or just more able to be present in the moment,” Pierre reflected. “So I don’t think that, for myself, intelligence is all that important. And I’ve also found it’s not that important in the people I want around myself. I want to be interesting—I’ve always wanted that since I was a kid and I still want it—but in the people that I meet, I find that it is much less important that a person be interesting than that they not be a pain in the ass. That’s why intelligence doesn’t carry a lot of weight with me.”

Seeking out people who are not a pain to be around takes on new importance in light of something else Pierre is trying to address in his life and his community. There’s a norm in our modern American society, he explained, to avoid addressing the difficult things that we don’t want to address—even when not addressing those things causes obvious problems. “If you talk to a foreigner, they say we talk about anything except sex, politics, and religion. And now we should add the word r-a-c-e. But my French students wondered what we do talk about if we didn’t talk about those three things.” That’s why, Pierre observed, in America, “we don’t know how to talk to each other.”

“The problem is, if you won’t talk about the things that touch most fundamentally on these truths—not facts, truths—then you can’t have a real connection with anyone, avoiding the things that are most important to you. That’s not good for [the other person’s] humanity, and it’s not good for how you feel about the relationship.”

Pierre suggests that this problem is the most important thing that we can tackle to make our lives and our society better: “To move a little bit closer to having real, honest conversations, to practice being good listeners, better able to navigate the dynamics of an effective conversation.” He regularly recommends a book called The Art of Civilized Conversation, by Margaret Shepherd and Sharon Hogan. It’s about how to have a conversation—how to listen, what to talk about first, what it’s worth talking about, how to politely end a conversation, how to change the subject, how to make a person feel at ease—all those things that cause so many of us to feel socially awkward and isolated.

“The book covers the basics of how to be around another human being, and I think we all need to spend more time on that,” he said. “A lot of us don’t know how to hold a conversation in the face of adversity. When you talk to somebody about something important—politics, sex, religion, race—and you find out they don’t agree with you…news flash! Somebody out there is going to disagree with you. When you hear somebody disagreeing with you about something you feel is important, you can’t help but feel attacked. So you need training—and practice—to have a conversation with someone and be able to hold it together.”

This was why Pierre said he thought that the theory of positive disintegration had something to offer us. So many of the plans we make, the values we hold, and the traits we come to praise—as we progress down the paths of our lives, we are sure to find out that some of them are no longer guiding us in the right direction. It was thanks to this ability to let go of what wasn’t working that Pierre has been able to find the right people and to build a career through which to apply his talents, giving the world something he thought it lacked.