The Cabin and the Hearth Fire

I have, as it were, my own sun and moon and stars,

and a little world all to myself.

— Henry David Thoreau

One may have a blazing hearth in one’s soul and yet no one ever

came to sit by it. Passers-by see only a wisp of smoke

from the chimney and continue on their way.

— Vincent van Gogh

In the exquisite solitude of his cabin in the Concord woods, Thoreau wrote his first book and gathered the living material for his magnum opus, Walden. Thoreau was not bothered by the isolation. “This whole earth which we inhabit is but a point in space,” he wrote. “Why should I feel lonely? Is not our planet in the Milky Way?” Viewed on this grand scale, he was as much a part of the human community as a parlour-hopping New York socialite. But his microcosmic “little world” was large enough for his wandering mind and feet. At first, readers are drawn into Walden by its Romantic premise, the rustic simplicity which we admire but do not seek to emulate. Readers stay, and are moved to emulate Thoreau in other ways, because of its extraordinary scope and clarity: from harvesting beans to building a chimney, his careful observations of Massachusetts wildlife to social conformity, education, and our relationship to Nature, Thoreau is our charismatic guide, by turns lyrical and pragmatic. He may have lived in a one-room cottage, but he commanded an empire of thought.

Let us contrast Thoreau’s happy wisdom with Vincent van Gogh, the painter whose visionary intensity and madness have become almost cliché. The quote above, from a letter to his brother Theo, suggests that Van Gogh did not know solitude, he knew loneliness, and knew it better than most. In place of Thoreau’s orderly microcosm—the sun, moon and stars of Walden pond—we have the Starry Night of Saint-Rémy, its celestial bodies scattered like droplets of fire across the canvas, luminous but in flux. The viewer feels that if they pause in front of the image too long, they too might melt into something else entirely. Van Gogh’s paintings convey a rapturous, almost violent response to the French countryside, of which Thoreau might have approved. But although he discovered a mature style in the cypresses of Arles and the wheat fields of Auvers-sur-Oise, Van Gogh never found himself. He died by his own hand in 1890. His final words: “The sadness will last forever.”

Both men had something extraordinary to offer, based on a personal experience of the transcendent. But why is Thoreau’s “little world” the image of restorative solitude, and Van Gogh’s “blazing hearth” that of genius misunderstood? Perhaps Van Gogh was simply mad, or Thoreau “favoured by the gods,” as the latter jokes in Walden. While I am not a psychiatrist or a priest, I believe we can find our causes closer to the earth. And in exploring the differences between Thoreau and Van Gogh, we can learn something about giftedness, personhood, and the flourishing or disharmony of the two in relation to community.

The Other Sage of Concord

The roots of resilience are to be found in the felt sense of being held

in the mind and heart of an empathic, attuned, and self-possessed other.

— Diana Fosha

Let us start with Thoreau. Walden is, at its core, a book about the benefits of healthy self-reliance and the means by which it is achieved. (Civil Disobedience can be viewed as a complementary perspective on the same topic.) But self-reliance cannot appear in a vacuum, and in Thoreau’s case, we can see the clear biographical outlines of its development. In 1837, Thoreau graduated from Harvard and came home to Concord, an earnest, bookish, and somewhat directionless young man of twenty. He soon met Ralph Waldo Emerson, fourteen years his senior and a rising star in the world of letters. Emerson was impressed by the quirky young scholar, encouraged his literary activities, and introduced him to Concord’s intellectual scene. One member of this circle was the poet William Ellery Channing, who became Thoreau’s closest friend and first biographer. Thoreau immortalized him as the Poet of Walden, who despite “deepest snows and most dismal tempests,” frequently tramped the six miles to Thoreau’s lodge, since as Thoreau explains, “nothing can deter a poet, for he is actuated by pure love.” In 1841, Thoreau joined Emerson’s household as tutor to his children, and all but officially his protegé, staying on and off for three years. His orbit began to wander, and after a sojourn in New York, Thoreau returned to Concord in 1844, restless, discontented, and wanting more space to experiment and flourish on his own terms. Channing joked: “Go out upon that, build yourself a hut, and there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive. I see no other alternative, no other hope for you.” Two months later, Emerson obliged Thoreau’s need, offering to let a parcel of land near Walden pond in exchange for clearing the woodlot of trees. Thoreau accepted the offer, built his cabin, and so the experiment of Walden began. In this sense, the book occurred within the literal physical confines of Emerson’s support.

But even if Thoreau had found another location to build his cottage and grow his turnips, Walden would still be a product of Emerson’s patronage. Thoreau first lived in the household of his benefactor, received his guidance, and one imagines, comfortably formulated his own ideas to the point where he felt the need and ability to go into the woods. As Diana Fosha succinctly puts it, resilience evolves when there is an “empathic, attuned and self-possessed other” in whom there is a “felt sense of being held.” Without resilience, how could Thoreau devour himself in a one-room hut in the middle of the Massachusetts backcountry? It was not the gods who favoured Thoreau, but Emerson: a self-possessed other who viewed Thoreau’s intellectual and personal development with paternal solicitude, who took him into his home, and when the time came, set him free. For all his joy in Nature, Thoreau’s self- reliance sprang from other sources than the Merrimack river or Flint Pond.

It was not the gods who favoured Thoreau, but Emerson: a self-possessed other who viewed Thoreau’s intellectual and personal development with paternal solicitude.

Broken Mirrors

We in the presence of a virgin creature with savage instincts.

With Gauguin, blood and sex prevail over ambition.

— Vincent van Gogh

A disordered work on his part, he accomplished nothing but

the mildest of incomplete and monotonous harmonies.

— Paul Gaugin

In 1853, while Thoreau put the finishing touches on his masterpiece, Vincent Willem van Gogh was born to a Dutch minister and his wife on the other side of the Atlantic. He was destined to be surrounded by cracked reflections of himself. He shared his Christian name with his grandfather, an uncle, and a sibling (also Vincent Willem) delivered stillborn a year to the day earlier, and whose tiny grave the young Vincent would pass as he walked through Zundert cemetery. But despite the appellative similarities, Van Gogh seemed a changeling among his conservative kinsmen. Passionate, impetuous, and big-hearted, Vincent alarmed his parents, who packed him off to boarding school at eleven, and disapproved of his choices in life and love when he returned. It seems Vincent never forgave being sent away, describing his childhood as “austere, cold, and sterile.”

Vincent’s one tower of strength was his younger brother Theo. A successful art dealer, Theo financed his brother’s creative activities and attempted (with notoriously limited success) to connect him to buyers. Their vast correspondence, a treasure for its window onto Vincent’s inner life, also testifies to the warmth and depth of their friendship. Despite his support, Theo could not play Emerson to his erratic and brilliant brother. Emerson did more than give Thoreau board, or introduce him to a literary agent; he gave direction, a community, and the approving fellowship of an exceptional mind. His small boat tacking furiously into a storm, Vincent needed direction and fellowship infinitely more than turpentine.

His small boat tacking furiously into a storm, Vincent needed direction and fellowship infinitely more than turpentine.

After abandoning his designs on the ministry in 1880, Van Gogh began his ill-starred search for an artistic mentor. First with his cousin Anton Mauve, then the Royal Academy at Antwerp, and finally the overlapping circles of Pointillism and Neo-Impressionism in Paris, nothing seemed to stick; he drank, smoke, argued, fell in love, collapsed, recovered, and despite these misadventures, assembled here and there the unconventional elements that would combine and explode into life in 1888. But he never acquired the blessings of a master or the imprimatur of a school. No doctrine could answer his inner necessity, and no master receive and enlarge this towering Dutchmen, still a stranger to himself, the way the eminence of Concord did with his protege.

This changed with Paul Gauguin, the first and last painter Van Gogh would call Master. In 1887, Van Gogh organized a small exhibit in Paris with fellow post-impressionists Émile Bernard and Louis Anquetin. Gauguin attended, lately arrived in Paris from Martinique. He was impressed by Van Gogh’s work, but not so much that he scrupled to offer one painting in exchange for two sunflower studies, a proposal Van Gogh eagerly accepted. This set the pattern: condescending encouragement on one side, met with the desperate longing on the other.

Sometimes, we cleave to the very things which will destroy us, mistaking in the lineaments of a face or gesture the phantasm of our needs met. In Van Gogh’s eyes, Gauguin acquired (perhaps by association with his Martinique subjects) the status of natural artist, “a virgin creature” beyond ambition, and the authentic guide he had been seeking all his life. In Van Gogh, Gauguin saw a struggling talent whose “disordered work” and “monotonous harmonies” he could improve, and, no doubt, his artistic cachet with them. Rather than being held firmly in the heart and mind, Van Gogh was grasped carelessly, like a paintbrush, in Gauguin’s hand.

The Sunflower

It’s certainly I, but it’s I gone mad.

— Vincent van Gogh

In February of 1888, Van Gogh left Paris for the warmer climes of Arles. In removing himself from the fashionable, avant-garde centre of the art world, he was taking the first steps towards devouring himself alive: a process where the self, like a chrysalis, is dissolved and creatively reconstituted. Thoreau needed the isolation of his cabin to turn into a butterfly; Van Gogh instinctively withdrew to rural France. But while the philosopher was ready for the transition, the painter was not. His conscious intent in coming to Arles was to found an art colony, a “studio of the South” which Gauguin would lead. On this pretext, he asked Gauguin to join him, and while “a vague instinct forewarned [Gauguin] of something abnormal,” the latter reluctantly agreed. With the Master successfully engaged, Van Gogh launched himself energetically into new projects. In August, he made a sequence of technically audacious sunflower paintings, radiant experiments in depth, patterning, and richly modulated hues of yellow which paid tribute to the sunflower studies earlier traded. They were, in short, a symbol of Van Gogh’s flowering creative self, his friendship with Gauguin, and a hope for their harmonious union. Accordingly, the sunflowers went on to decorate Gauguin’s bedroom at the Yellow House, 2 Place Lamartine, where they would share rooms.

When Gauguin arrived in October, he settled immediately into his role as Master, the superior term of an inequality. His journals tell us he found Van Gogh “floundering about” in the “full current of the Neo-Impressionist school,” and charitably “undertook the task of enlightening him.” While he allows that, “from that day, my Van Gogh made astonishing progress,” the pupil was still “my Van Gogh” and progress “from that day”: a project which redounded to Gauguin’s credit and not Vincent’s. But even these claims are inflated. It is clear from the slew of pre-October masterpieces that Van Gogh was not drowning in any stylistic preconceptions, but rather, the flood of his own genius. He did not need painting tips, much less the narcissistic posturing we find in Gauguin’s journals. Van Gogh needed this man he so respected to give him his due. He was like a huge and lonely sunflower in the middle of a field, dangerously weighed down by the visions in its head, and wanting the loving hand of a gardener, or the company of other tall sunflowers, to help it grow straight.

Van Gogh was like a huge and lonely sunflower in the middle of a field, dangerously weighed down by the visions in its head, and wanting the loving hand of a gardener, or the company of other tall sunflowers, to help it grow straight.

In December, 1888, the two men painted portraits of each other. Gauguin’s portrait shows Vincent in a dusty yellow suit at work on one of his still lives, arm rigidly before him, almost robotically absorbed in his work. Van Gogh was revolted, declaring “it’s I gone mad.” He did not disclaim the likeness, but saw how Gauguin distorted at the same time as reflecting. Like wandering unknowingly into a funhouse, a warped likeness can be more dangerous than no likeness at all. Van Gogh’s portrait of Gauguin gives us a three-quarter view from behind, as if caught in the act of leaving or turning away. The drooping eyelids, aquiline nose, tapering beard, even the slight, instructional tilt of the head, suggest hierarchy and disdain. A line divides the room, with a green region (matching Gauguin’s jacket) leaning threateningly over the yellow. Inside the green is a small yellow square, reminiscent of the sunflowers in Gaugin’s bedroom. That square, in its mingled desolation and hope, is more articulate than a hundred letters to Theo.

The tension between green and yellow reached a crisis point on December 23, in one of the most sensational episodes in the history of art. Van Gogh approached Gauguin in the street, brandishing a razor; Gauguin stared him down; Van Gogh fled to the Yellow House, began to hear voices, and cut off his own ear. We need not invoke bipolar disorder or acute intermittent porphyria to explain what happened between the two men. Van Gogh’s murderous feelings towards Gauguin, his sense of betrayal and narcissistic misuse swelled by a lifetime of inadequate reflection, had no outlet. In a classic neurotic reversal, he was forced to turn them on himself. But perhaps it was a double-sided gesture, and the auricle not only invested by murderous rage, but also that part of himself which had been innocently given over to the Master—the yellow square, swallowed up by the green—and which must be finally yielded. The ear may have been the price of freedom.

Disintegration and Containment

The dynamisms active in these departures from psychic equilibrium

also contain the primary elements of creative development.

— Kazimierz Dabrowski

Ellery Channing’s quip about the “grand process of devouring yourself alive” anticipates Kazimierz Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration by 120 years. Dabrowski’s basic idea was that personality evolves in distintegrative fits and starts, moments of inner crisis and resolution in which the self is reorganized. These “departures from psychic equilibrium” are accompanied by instability, doubt, and even psychosis, but if properly concluded, they are “positive”: the re-integrated person forms a richer and more developed whole. According to Dabrowski, how far a person can ascend this ladder of self-development is determined by internal factors—the development potential, comprising inborn talents, “overexcitability,” and an autonomous drive towards growth—and exogenous conditions such as education and trauma. The intricacies of the framework will not concern us. But we can understand the cabin by Walden Pond, and the colourful lodgings at 2 Place Lamartine, as scenes in this drama of crisis and resolution.

Both disintegrations were effective, creatively speaking. Thoreau wrote his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, and laid the groundwork for Walden and Civil Disobedience; the protege walked into the woods, but the philosopher emerged. Van Gogh, on the other hand, perfected his alchemy of colour and brushwork, producing masterpieces with the careless fecundity of a child plucking blossoms from an overflowing bush. But viewed through the human lens, the outcomes could not be more different. The Titan of Post-Impressionism was born in Arles, but so was the Madman and his sacrificial fragment.

We have discussed how Emerson provided an attuned, selflessly interested other who could reflect Thoreau as he was. This “as he was” or true seeing helped erect the stable foundation on which Thoreau could change who he was, and become something new. True seeing provides a sort of container for disintegration: like a warm hug, it is a matrix which limits the throes of disequilibrium and from which re-integration can proceed. This is precisely the role of a chrysalis when the caterpillar dissolves. Instead of a stabilizing figure like Emerson, Van Gogh had Gauguin, in whom he was warped and finally split like the funhouse mirrors. When the crisis came, he could not put himself back together. Van Gogh lived for another two years, and produced astonishing work, but he was never whole. The butterfly cannot form unless the chrysalis is intact. It will leak its essential substance and perish.

This points to a special need for grounding and containment when tremendous creative forces are at play. Van Gogh did not paint by numbers. His art consumed his life, projecting him onto the canvas, as it were, beside those great swirls of cobalt blue and yellow lead chromate. Dabrowski uses the term “overexcitability” for this quality of intensely lived experience, but differences of degree are important here. An enthusiastic Sunday dabbler can paint a cabbage patch without concern for their ego boundaries, but for someone like Van Gogh, the cabbage patch might be an ordeal, an ecstasy where the self is easily misplaced among the vegetables. Unless such natures are grounded, there is danger in ordinary things.

Van Gogh did not paint by numbers. His art consumed his life, projecting him onto the canvas, as it were, beside those great swirls of cobalt blue and yellow lead chromate.

Calling Down the Lightning

The best lightning rod for your protection is your own spine.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson

It was essential for me to have a normal life

in counterpoise to that strange inner world.

— Carl Gustav Jung

“Grounding” suggests a different metaphor. Sometimes we are struck by lucky inspiration, the proverbial bolt from the blue. But sometimes we are equipped, by temperament, circumstance and preparation, to call down the lightning at will. There are huge energies in the storm at the mountaintop, and they can be harnessed to perform amazing feats, but if we summon the maelstrom at the wrong time, it can destroy us.

I have had my own experience of these dangers. When I was sixteen, I took a high school philosophy class, reading excerpts from the Western canon with dusty, rote assiduity that left me unmoved; the knowledge had died, and the canon served as its tomb. I wrote my essays and forgot them immediately. During the winter break, my brother and I bussed from Melbourne to Canberra to stay with a family friend. As we rolled through the gentle pasturelands of New South Wales, I heard a rumble, distant but growing, and by the time I arrived in Canberra, the storm had broken. I realized with a kind of horror that philosophy was not imprisoned in those moldering classics, the quibbles and quarrels and parlour games. It was everywhere: in the living mysteries of human existence, social organization, time, chance, clothing, food, jurisprudence, the grain of cedarwood or a blue slant of October light. I need only inquire closely into the nature of an object—any object—to liberate its Pandora’s box of unanswerable conundra. Like the Aleph in Borges’ story, each object was a portal to infinity.

In the scheme of my life, this Alpha was almost comically premature. Attending public school in a rough, blue-collar neighbourhood, I was considered “bright” and therefore left to my own devices. At home, years of trauma and a messy custody battle had left me alienated and enraged. When loneliness and anger stalk the long halls of the soul, there is no room for revelation; I was too small to contain the Alpha, and had to leave it where I found it. In terms of our analogy, I had no lightning rod, no way for the psychic energy of the storm to be sustained, directed, and safely discharged. Van Gogh’s tragedy was not merely the disappointed need for fellowship and true seeing: it is that the lightning came anyway, and lacking a proper conduit, it tore him apart. He was tall metal in a storm, and the bolt went straight to the hearth.

Attending public school in a rough, blue-collar neighbourhood, I was considered “bright” and therefore left to my own devices. At home, years of trauma and a messy custody battle had left me alienated and enraged.

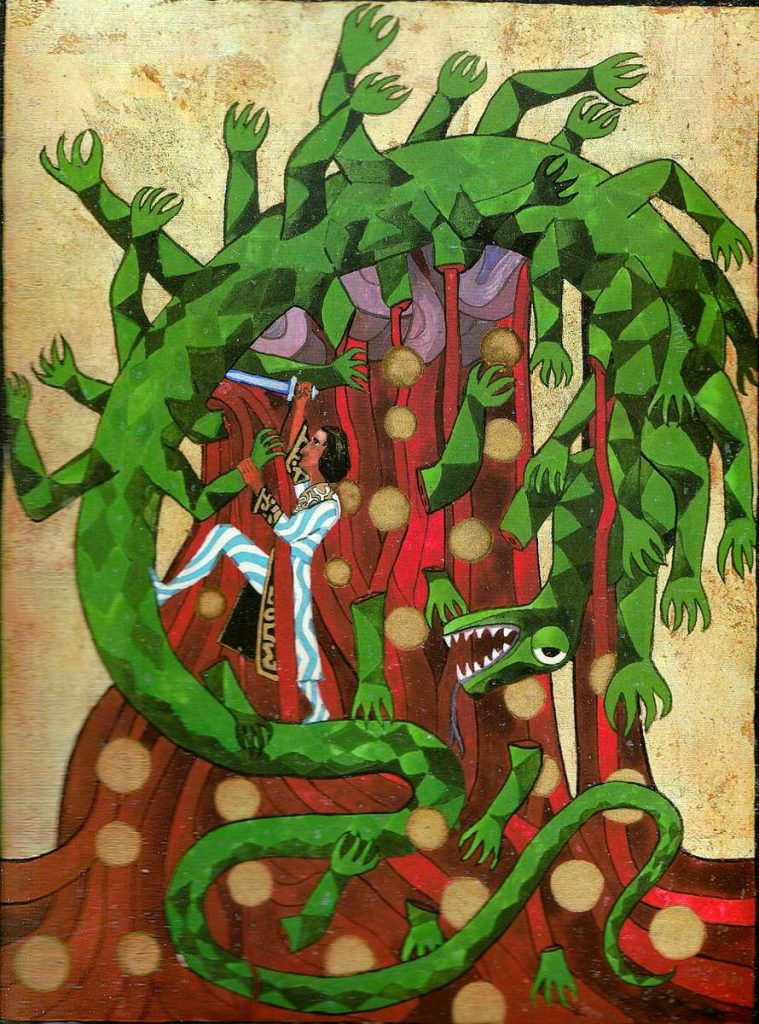

Swiss psychologist Carl G. Jung offers a contrasting instance of successful disintegration. After his famous break with Sigmund Freud in 1913—an Emersonian patron he eventually outgrew—Jung became apostate in the psychoanalytic community, and plunged into a crisis of personal and professional self-doubt. He too heard a storm, distant but rumbling, and as he withdrew into the seclusion of his home and practice, it arrived at his doorstep. But he was ready to summon lightning in its most spectacular form, embarking on a sequence of hallucinatory voyages into the collective unconscious. They changed his life and the intellectual landscape of the 20th century with it. His visions form the basis of The Red Book: Liber Novus, a lavishly illustrated chronicle of his descent, but also analytic psychology itself, Jung’s alternative to the Freudian paradigm. Instead of being the arena for the antisocial drives of the Id, for Jung, the unconscious was the seat of the Self: a repository of regenerative mental energies, an instinct towards wholeness, and the collective, mythopoetic patterns he termed “archetypes.” Jung had wrested the sun from the belly of the dragon, carrying away not only the creative prima materia, but the stable personhood needed to transform it into the opus of a full life. Van Gogh never had that chance.

Jung had wrested the sun from the belly of the dragon, carrying away not only the creative prima materia, but the stable personhood needed to transform it into the opus of a full life. Van Gogh never had that chance.

While Jung was following this program of mythopoetic psychosis, his family life and busy therapeutic schedule continued; they provided a “counterpoise to that strange inner world,” the ballast of an earthy reality in which he ate bread, treated his patients, and played with his children. The house was safely insulated from the lightning rod. Thoreau too was tethered to reality, not only by his ties to Emerson and the Concord intelligentsia, but the precepts of simple living, a Transcendentalist ethic which emphasized a healthy connection to Nature. Both men had one foot on the ground.

For the extremes of “development potential,” storms are only temporarily avoidable. I escaped the Aleph of philosophy, but found portals to the infinite in visions, tempests of poetry, mathematics, the patterns of decay in the alley behind my apartment. Sensing a disintegration the ego might not survive, I have mumbled my excuses and moved on, content to damp the intensities rather than risk annihilation. But in the end, we cannot escape who we are, or who we are called on to become. Some of us must eventually devour ourselves alive. If these intensities render the ordinary dangerous—if, say, growing beans becomes an act of rebellion, or a wheat field eternity—the key is to engage with them strategically. First, we must find self-possessed mentors and a community of feeling in which we are held firmly and seen truly; second, we must eat the bread of the real world, and walk in its mud while our thoughts dance far above. Only then should we journey to the mountaintop and invoke the lightning. Only then will we be truly solitary and not alone, grounded and contained, for a connective tissue joins the hut on the summit to the star-flung fields of the receptive earth, where the farmer and his wife sit down to dinner, and the dog snores by the fire, dreaming of who knows what.