If you’re interested in adult giftedness or high IQ, the odds are good that you’re the type of person who does your research. This means you may have become aware of one unfortunate fact: there really isn’t that much formal scientific research on the impact of high IQs on adults’ lives.

Fortunately, there is a small but growing group of researchers dedicated to filling this knowledge gap. One of them is Dr. Sonja Falck, author of Extreme Intelligence: Development, Predicaments, and Implications, which we previewed in our last issue. The book is part of her effort to shed light on some of the social and relational questions that often lead people to explore the question of adult giftedness (or, to use terms that Falck prefers, “high ability” or “high IQ,” since “gifted” is nothing but a nebulous value judgment).

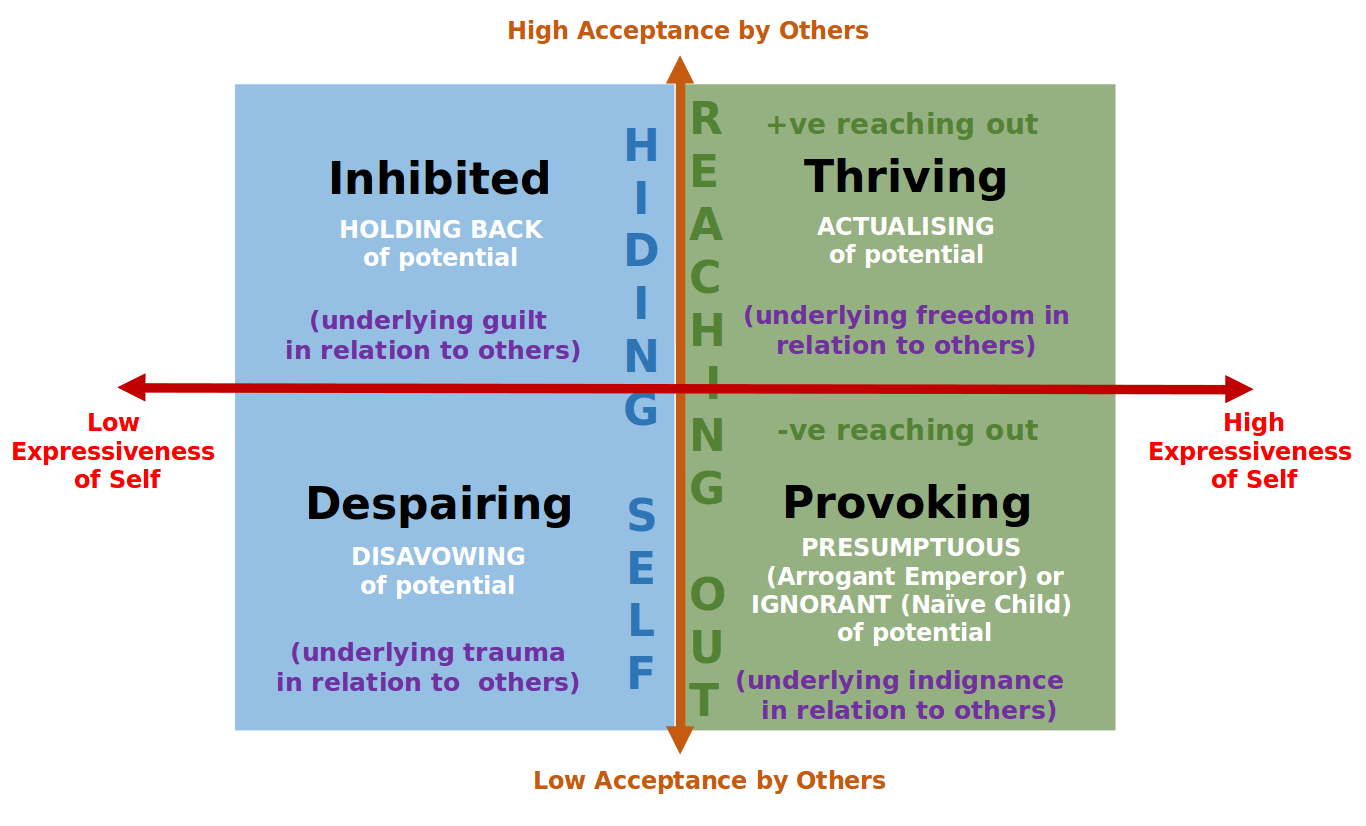

At the core of her recent book is a model that she has developed to explore the reasons high IQ adults may or may not thrive, with a particular emphasis on issues of belonging. The model, which she calls the High-IQ Relational Styles Framework, compares two variables: expressiveness of self and acceptance by others. Placing the former on the X-axis and the latter on the Y gives us four quadrants that broadly represent modes of interpersonal living: Thriving, Inhibited, Despairing, and Provoking.

These quadrants could inform a lot of the conversations I’ve had with high-IQ adults, many (though certainly not all) of whom feel at least somewhat lonely or isolated. It was with this in mind that I sat down to talk with Dr. Falck about how she developed her model, how she hopes it will be used, and the next steps in research into the well-being of this unique population.

A Study of High IQ Adults

Falck’s model is grounded in her extensive education and experience with this population. She is a UK-accredited psychotherapy trainer with a private practice of her own, and she also holds an academic post at the University of East London. In her private practice, she focuses on high-IQ clients, which has provided her with what she called “an amazing feedback loop” for her writing on this subject. “What I’m researching and writing about I can then use in my consulting, and my clients bring me more material that adds to what I’m researching and thinking about. So I’m constantly hearing from real human beings who are living with this,” she told me.

At the same time, when she did the research that provided the foundation for her model, she followed a formal process (namely Kathy Charmaz’s Constructivist Grounded Theory research methodology). She began by conducting interviews with Mensa members, a group she selected because they’ve already taken standardized intelligence tests and scored in the top two percent. Of course, as she acknowledged, this sample doesn’t provide a perfect snapshot of the high-IQ adult population: in the United Kingdom, the top two percent of the population would be about 1.3 million individuals, but there are only 24,000 members of British Mensa. “That’s a tiny subsection of the people who are probably very high IQ,” as she observed.

She also noted that the ninety-eighth percentile (equivalent to IQ 130 on most tests), though commonly used as a threshold for “giftedness,” may seem somewhat arbitrary. “IQ 130 is where I put my boundary because you’ve got to have a boundary,” she explained. Her experience, however, has led her to believe that it is indeed the point where the sorts of life trajectories she’s studying begin to show up. “What I have seen in my practice is that clients who have intelligence in that range, as ‘low’ as 130, experience the kind of interpersonal challenges that I’m talking about in the book. But of course, the range begins there, so I’m also dealing with people with measured IQ of 160 or 180.”

Outsiders Born—or Made?

A key theme that has emerged from Falck’s study of this top two percent is that of feeling like an outsider. She highlights this element in her model with the “acceptance by others” axis, and she explores the theme in depth in Extreme Intelligence. Belonging, of course, matters to every one of us human beings, and we often go to considerable lengths to find it. To quote from the book, “Ingram & Morris (2007) explain that it is human nature to look for similarities in others and to identify with others, who one then groups together with. They term this ‘homophily’ and place it at the core of socialisation. […] Experiencing alikeness, or twinship, with others, is what produces a sense of belonging with those others.” (81)

But some people, after an unfruitful struggle to find such alikeness with others, opt to embrace their lack of twinship as a core part of who they are. Third Factor columnist Benita Jeanelle, for instance, gave us an example in her recent column on “self-othering.” This is a path that Falck has seen many times in her work:“I think it’s an interesting ambivalence,” she told me, “whether somebody wants to feel accepted and understood, or whether they are protective of being outside—even if being outside hurts—because it’s become a part of their identity.” As she wrote in her book, “Once you have become familiar with experiencing yourself as different and not fitting in, being different can become part of your identity so that it becomes uncomfortable to think you could belong with or be like others.” (150)

Once you have become familiar with experiencing yourself as different and not fitting in, being different can become part of your identity so that it becomes uncomfortable to think you could belong with or be like others.

Dr. Sonja Falck

Extreme Intelligence touches on a theory developed by evolutionary psychologist Satoshi Kanazawa that argues that people with very high IQs are an anomaly—but that, in living on the margins, they play a socially useful role. They dedicate themselves to solving difficult problems rather than being in the midst of community; they are not satisfied with a focus on subsistence and reproduction. Falck was critical of much of what Kanazawa has written, but found this particular idea thought-provoking. If this theory is correct, it would help explain why people with high IQs often focus on broad social problems at the expense of more personal goals. “For a person like that,” she said, “there is quite a tension: do they want to keep set apart from the main group because they feel that that is their purpose? And their purpose is what defines them.”

If such people are dedicated to truly looking at themselves objectively, however, they may find their perceived utter difference is not as airtight as they have come to believe. Falck relayed the story of a client who disliked the other women in her workplace because they had conversations she said she absolutely could not relate to: “They were talking about buying clothes or makeup,” Falck explained. “She said that’s just so meaningless, and she feels like this huge outsider. [Later], I enquired about her chosen friends who she feels she does get on with. What kinds of conversations do feel good for her? Eventually, it came out that sometimes they too talk about clothes because they also buy clothes, and sometimes you talk about that with friends.”

Falck’s client hadn’t made this connection because at work, for some reason they would go on to explore, “she wanted to see herself as an outsider. There is so much overlap in us as human beings. We have to eat; we have to sleep. So if we can talk about things like that, we can talk to anybody about them. But often, a very high IQ person doesn’t want that. They want to have an identity of being above all of that.”

What might be underlying such a desire to separate from such mundane conversations and (some of) the people who engage in them? Could it be, I asked, that they have other social needs that are not being met, and that they engage in this self-othering as a response?

Falck said she thinks this is a fair frame. “If you don’t feel like you’re being appreciated for something that feels quite core to you, then you might feel standoffish and not really want to reach out to other people to meet them where they’re at,” she said. “Whereas if you feel satisfied and relaxed, then you probably talk more readily about stuff that could be quite ordinary—as well as wonderfully complex things.

If you don’t feel like you’re being appreciated for something that feels quite core to you, then you might feel standoffish and not really want to reach out to other people to meet them where they’re at.

Dr. Sonja Falck

“Even if they are an outlier,” Falck continued, “even if they have a purpose for being marginal to the community and need to protect their independence of mind and not get too involved with day-to-day social chit-chat and so on, even people like that want to have a friend. Or a partner. Or some sense of belonging.”

But because of the difficulty in finding this twinship, a lot of people with a very high IQ, said Falck, simply accept their lack of belonging and become depressed. If they realize the role of their unusual mind in their struggles, it opens the door to addressing this issue. Falck said this is what drives people to join organizations like Mensa. “All the people I’ve met who have become members of Mensa come to take the test for reasons like that. They have recognized something about themselves that doesn’t fit in. They’ve got comments along the way that point to them being very smart. And they hear of a place like Mensa, and they want to try that test: ‘Am I one of them?’”

Of course, as she mentioned earlier, only 24,000 out of the estimated 1.3 million with a 130+ IQ in the United Kingdom end up pursuing this path. The other 1.276 million find other paths: they may have a support network in a family (where many people are like them). They might find a workplace full of people like them. They might find lifelong friends when they get to university. Some of these people may know they have a high IQ; others may not.

But those who lack this self-knowledge often follow another path, and it’s not a happy one. “You get some who never get identified and feel there’s something wrong with them,” Falck said. “I get that a lot. They think they’re stupid, because they couldn’t understand why other people found a task difficult or complex, so they thought they must not be seeing something profound in this task. There are a bunch of people living with that self concept.”

Developing the Model

It was with this diverse mix of paths in mind that Falck developed her four-quadrant model. She chose the two fundamental axes of expressiveness of self and acceptance by others because of the nature of the problems that her clients seek to solve. “As a psychotherapist, my speciality is in improving relationships, personal and professional,” she explained.

Some who have struggled to accept themselves when they don’t fit into the mainstream may bristle at seeing the emphasis on “acceptance by others” in Falck’s model. One Third Factor reader asked ahead of our interview whether focusing on autonomy and choice might be preferable to accommodating or adapting to others.

Falck responded by emphasizing that her model has two axes: one is indeed acceptance by others, but it’s balanced against expressiveness of self. “What my model is saying is that none of us exist in a vacuum. I’m focusing on the interaction between expressiveness of self and acceptance by others because I see them as hugely co-influencing each other. If someone’s expressing themselves in a way that is obnoxious—if they’re fully self-expressive, but they’re offending people around them all the time—there will be a cost to them in the form of repeated rejection. Then they might find they can’t find a way to express themselves. Even if you’re going to be a wonderful writer, sitting alone by yourself, someone’s got to read it! My model is about recognizing the way you might express yourself, and the way people might react.”

She added that some people may actually have positioned themselves in the quadrant she’s labeled “Despairing” by choice, and that she does not intend to criticize this. “You get all sorts of nihilistic authors and artists who create wonderful work through their despair. If someone wants to be in that quadrant, I’m not saying they need to change. Where my work slots in is with people who are not thriving—and who want to thrive.”

Importantly, even if someone chooses to learn skills that can help them increase their acceptance by others (or their expressiveness of self!), it’s always a choice whether to apply them or not. “If you are in a group who are expressing values and interests that you feel averse to, then you probably are going to choose to not use your social skills to make it look like you belong—because you don’t want to belong with that group. But if there is a group that you want to be identified with, how can you interact with them in a way that you would enjoy? That’s where my work would come in.”

If you are in a group who are expressing values and interests that you feel averse to, then you probably are going to choose to not use your social skills to make it look like you belong. But if there is a group that you want to be identified with, how can you interact with them in a way that you would enjoy?

Dr. Sonja Falck

The four quadrant model can also be useful when a person’s environment or circumstances change. Falck gave the example of a client who was thriving in their university years, but later found that they’d moved somehow into the inhibited quadrant. The model can help such a person understand how and why that happened and how they can get back to where they’d like to be.

Essentially, said Falck, people have tried three ways to address the problem of belonging: changing the self, changing the environment, or changing the interface between the person and the environment. And she makes clear in her book that the first path is not a promising one: “Whilst a person’s nature can be hidden, or disavowed, it cannot be fundamentally changed. The price of attempting such change is usually paid in deteriorating mental health.” (65)

Where Do We Go From Here?

When Falck looks at the small but growing academic field studying the lives of high IQ individuals, she sees a lot that needs to be done. One basic problem is that several fields focus on elements of this topic—human intelligence, gifted education, expertise—but there’s not much interaction between them. “When you read books on each of these fields, they very often don’t refer to each other,” she said.

When I asked her how we might bridge these gaps, Falck described a broad study she would love to conduct someday: it would involve a very large, international sample of participants representing all parts of the intelligence bell curve who would undergo a battery of tests, including IQ tests, autism spectrum screenings, and other mental health and personality measures—including questions that would test her model in more depth, revealing how high IQ people relate to others, and whether there really are differences between various IQ bands. Participants could answer questions designed to provide data about how they feel about themselves and how they relate to others, illuminating whether the High IQ Relational Styles model really does explain relational difficulties unique to high IQ populations. She also would like to dive into questions about the unique experiences of highly intelligent women.

The need for additional research into this population is clear. Falck collected the names of several possible co-researchers and subjects when she presented her model at the 2019 Supporting the Emotional Needs of the Gifted conference in Houston, so we may yet see it realized.

In the meantime, Falck’s work offers high IQ adults a tool that might help them make sense of their unusual challenges and to grow toward thriving—whatever they each determine it means to thrive.