In the last issue of Third Factor, I explored the early years of Nobel Laureate Maria Sklodowska Curie through the lens of the Kazimierz Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration. Part I focused on what Dabrowski would have called her developmental potential, with a particular emphasis on the overexcitability that was so evident in her youth. In Part II, we’ll look at where that overexcitability leads, exploring the choices that she made to get on the path that would ultimately lead to two Nobel Prizes.

It was not an easy path. Maria would have to overcome loneliness, heartbreak, humiliation, anxiety, and deep depression.

We rejoin Maria as she makes the pact that sets this chapter in motion.

Sisters’ Pact

Both Maria and her sister Bronya dreamed of going to Paris to study at the Sorbonne. After completing their education in France, both women hoped to return to their beloved Poland: Maria as an educator and Bronya as a doctor. So Maria made a pact with her sister: Maria would work to support Bronya financially while Bronya was in school, and Bronya would help Maria after Bronya completed her studies. At first, Bronya was adamantly against Maria’s plan. It was through Maria’s empathy and identification with her sister—two level IV dynamisms—that she was able to convince Bronya to go along with it: that is, by understanding Bronya’s motives and feeling motivated to help her achieve her plans. We also see the third factor, also a level IV dynamism, at work. The third factor refers to the role of our conscious choice as we develop our own autonomous hierarchy of values; this was the force that led Maria to realize not only what was essential for her development, but also enabled her to look into look into the future and plan for it.

Disappointing Experiences

And so Maria started to look for a well-paid job as a governess to teach children of well-to-do families in Poland, supporting Bronya from afar. Unfortunately, the position she found teaching the children of a family of lawyers would lead to disappointment.

In a letter to her cousin Henrietta, dated December 10, 1885, Maria wrote of her employers,

They pose as liberals and, in reality, they are sunk in the darkest stupidity. And last of all, although they speak in the most sugary tones, slander and scandal rage through their talk—slander, which leaves not a rag on anybody… I learned that the characters described in novels really exist, and that one must not enter into contact with people who have been demoralised by wealth.

Maria’s letter demonstrated her positive maladjustment—that conscious rejection of the attitudes and behaviours that are the norm in our social environment but that conflict with our individually chosen higher values. Maria, who grew in the family of love, care, and respect, found the malicious gossip, stupidity, and vulgarity of her employers disgusting. By actively rejecting that kind of behaviour, she demonstrated her understanding that the privileges of birth and wealth did not grant character or morality. Her pride in her family’s values and her education grew.

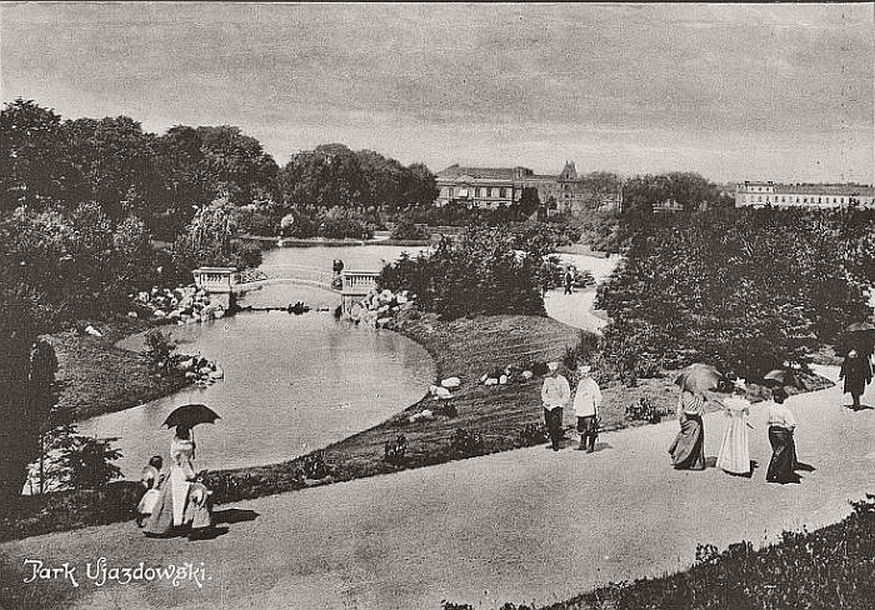

Maria concluded that she could not remain with the family of lawyers. And so, on January 1, 1886, she left her family and friends behind in Warsaw and journeyed by train and sleigh to a new job in a distant province. She would be teaching the children of an agriculturist who ran a beet sugar factory in the village of Szczuki, one hundred kilometers north of Warsaw.

A month after her arrival, Maria wrote to Henrietta about her early experiences at this new place. She was satisfied with her new employers and even made friends with their eldest daughter, Bronia. But she criticized the country way of living:

In this part of the country nobody works; people think only of amusing themselves… One week after my arrival they were already speaking of me unfavourably because, as I didn’t know anybody, I refused to go to a ball at Karvacz, the gossip centre of the region…

In this part of the country nobody works; people think only of amusing themselves… One week after my arrival they were already speaking of me unfavourably because, as I didn’t know anybody, I refused to go to a ball at Karvacz, the gossip centre of the region.

Maria Sklodowska

In this letter, we see once again Maria’s positive maladjustment. She could not accept the conventional life of the village.

Teaching Peasant Children

One day, as she walked through the village, Maria met some poor young peasants.. Moved by the circumstances of their lives, Maria felt a powerful desire to improve their lives—and to put the progressive ideas she had gained from her study of Positivism into real-world practice. She therefore decided that she would teach the children to read and write. On September 3rd, 1886, in the letter to Henrietta, Maria described her educational activity:

Bronka and I give lessons to some peasant children for two hours a day. It is a class, really, for we have ten pupils. They work with a very good will, but just the same, our task is sometimes difficult. What consoles me is the results get better gradually, or even quite quickly. Thus I have pretty full days—and I also teach myself a little or a lot, working alone.

In Maria’s decision to teach the children, we see the third factor continuing its work. It is the source of her internal motivation and of her desire to turn her chosen ideals—in this case, represented by the teachings of Positivism—into action.

We also see authentic responsibility, another level IV dynamism, at work. This dynamism involves conscious choice of social tasks (in this case, teaching poor children) that arises from her emotional, intellectual, and imaginational overexcitability.

Dream and Solitary Studies

Maria still dreamed of studying in France. She devoted every night to her study of sociology, physics, and mathematics. She did so without any direction or advice—only with her stubbornness and determination.

In December 1886, in a letter to Henrietta, Maria described her approach to these solitary studies:

At nine in the evening I take my books and go to work, if something unexpected does not prevent it…I have even acquired the habit of getting up at six that I work more…I read several things at a time: the consecutive study of a single subject would wear out my poor little head, which is already much overworked. When I feel myself quite unable to read with profit, I work problems of algebra or trigonometry, which allow no lapses of attention and get me back into the right road.

In Maria’s dedication to her dream, we see how the third factor directed her growth, shaping her into the independent scientist she would become.

A Humiliating Experience

During her time in the countryside, Maria and the son of her employers fell in love. The couple planned to get married. The young man’s parents, however, didn’t approve of their plans because Maria was too poor for their favourite son.

Maria felt humiliated by their rejection, making it difficult for her to stay there. But she had promised to support her sister’s study in Paris, so she needed money. There was, therefore only one solution: to distance herself emotionally, swallow her pride, and continue her work as if nothing had happened.

In the series of the letters to her family, Maria expressed openly how deeply wounded she was by the act of rejection. On March 9, 1887, she wrote to her brother Joseph, of her depression, stating that “for now I have lost the hope of ever becoming anybody.” Without hope for herself, she transferred her ambition to her sister and brother. In this shift of her focus, we see the dynamism inferiority to oneself. This dynamism includes the attitude of compassion, empathy, and the need to help other people in their problems.

In another letter to her brother a few months later, Maria expressed strong feelings of dissatisfaction with herself linked with depression and anxiety. She wrote,

I am very much afraid for myself: it seems to me all the time that I am getting terribly stupid—the days pass so quickly and I make not noticeable progress. […] I only want the conviction that I am being of some use…I hope that I shall not disappear completely into nothingness…

I am very much afraid for myself: it seems to me all the time that I am getting terribly stupid—the days pass so quickly and I make not noticeable progress. I only want the conviction that I am being of some use.

Maria Sklodowska

At the end of 1887, in the letter to Henrietta, Maria wrote about her future plans and dreams. These were now much more humble than they had been before her humiliation. She didn’t mention studying in Paris. Instead she wrote, “My plans for the future are modest indeed: my dream, for the moment, is to have a corner of my own where I can live with my father.” But, she dreamed to be independent again, to leave the village, and to return to Warsaw where she could teach in a girls’ school. Being independent is expression of autonomy, a level IV dynamism that involves gradually gaining independence from the lower levels of internal and external reality. For Maria, the lower level of reality was her life in the village; and to gain independence, she would have to leave.

But for the time being, Maria continued her work at the village—and her depression deepened. On March 18, 1888, Maria opened up to her brother again, expressing her dark emotional state. “Write to me, well and long, everything that happens at home,” she wrote to him. She was longing to escape to Warsaw even for a few days, to be free from the icy atmosphere of her employers’ residence, as well as the strain of continually controlling her own words and even facial expressions. She was emotionally exhausted. As she wrote to her brother, “I say nothing of my clothes, which are worn out and need care—but my soul, too, is worn out.”

Almost eight months later, on November 25, 1888, in a letter to Henrietta, Maria was able to reflect on the darkness that hung over her in village life:

I feel everything very violently, with a physical violence, and then I give myself a shaking, the vigour of my nature conquers, and it seems to me that I am coming out of a nightmare… First principle: never to let one’s self be beaten down by persons or by events.

I feel everything very violently, with a physical violence, and then I give myself a shaking, the vigour of my nature conquers, and it seems to me that I am coming out of a nightmare… First principle: never to let one’s self be beaten down by persons or by events.

Maria Sklodowska

Maria was counting the days until return to Warsaw and her family. She desperately needed a change in her life. As she wrote,

[T]he need for change, of movement and life, which seizes me sometimes with such force that I want to fling myself into the greatest follies, if only to keep my life from being eternally the same. Fortunately, I have so much work to do that these attacks seize me pretty rarely. It is my last year here; and I must therefore work all the harder, so that the children’s examinations will go well…

This letter expresses the operation of the dynamism subject-object in oneself. This level IV dynamism encompasses self-observation, self-evaluation, and a conscious need for developmental change. Due to this dynamism, Maria turned her attention to her emotional state, exploring to her thoughts and her need for change.

As Maria’s time in the village drew to a close, she began to recover from her depressive feelings. “My head is so full of plans that it seems aflame,” she wrote to her friend Kazia on March 13, 1889. “I don’t know what is to become of me.” Maria’s letters illustrate the turbulent emotional process that her rejection stirred up. Because of her emotional overexcitability, the intensity of her reaction was tremendous. She lost her ambition, became dissatisfied with herself, experienced anxiety and depression, and let go—at least temporarily—of her dreams. At the same time, as part of this process, the depressed Maria was able to confront the lower level of reality—and became aware of the higher level. She transferred her ambition to her family, empathized with her father, continued to support her sister, and discovered the importance of independence in her life. She was able to reflect on her emotional state and on the need for change in her life. In this way, during this two-year period, Maria’s behaviour was guided by dynamisms of the third and fourth level of positive disintegration.

My head is so full of plans that it seems aflame. I don’t know what is to become of me.

Maria Sklodowska

A Long-Awaited Decision

One day in March 1890, after returning to Warsaw, Maria received an unexpected letter from her sister, Bronya. She was offering Maria the opportunity to stay in her new home in Paris for the coming year. Bronya’s letter asked Maria to make a decision she had been preparing to make since before she came to the village.

But Maria’s traumatic experiences made her extremely careful and sacrificial. She was prepared to give up her dream for the sake of her father and her siblings. On March 12, 1890, Maria wrote back to Bronya:

I dreamed of Paris as of redemption, but the hope of going there left me a long time ago. And now that the possibility is offered me, I do not know what to do…I am afraid to speak of it to Father: I believe our plan of living together next year is close to his heart, and he clings to it. On the other hand, my heart breaks when I think of running my abilities, which must have been worth, anyhow, something….

In the end, two events in Maria’s life conspired to push her to Paris.

The first of these was Maria’s experience in a real laboratory. Maria’s cousin Joseph Boguski was the director of the Museum of Industry and Agriculture; Boguski let Maria develop her “taste for experimental research” in the museum’s laboratory during evenings and weekends. This experience brought light into her dark life. As she finally discovered her vocation, she felt alive once more.

The second event was the unexpected meeting of her love—the son of her former employers. Up to that point, Maria had believed that she still loved him. Upon seeing his weaknesses, hesitations, and fears, however, her emotional link to him was finally broken. She was finally completely free.

In September 1891, Maria had an awakening. She finally knew what her next step should be. On September 23, she wrote, “…Now, Bronya, I ask you for a definite answer. Decide if you can really take me in at your house, for I can come now. I have enough to pay my expenses…It would be a great happiness, as that would restore me spiritually after the cruel trials I have been through this summer, which will have an influence on my whole life—but, on the other hand, I do not wish to impose myself on you.”

In November 1891, Maria left Poland for Paris in order to finally realize her dream. It was the culmination of her increasing conscious, self-determined, autonomous, and authentic development—in other words, it was the result of the third factor.

The Dynamic Path

As illustrated in Part I of this series on Maria Sklodowska Curie, Maria was equipped with a very strong developmental potential. All the forms of overexcitability were present, with intellectual, emotional, and imaginational the strongest. Throughout Maria’s development, her overexcitabilities underwent differentiation and produced a variety of dynamisms, as described by Kazimierz Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration.

During her late adolescence, dynamisms from the fourth level of positive disintegration guided Maria’s behavior. These dynamisms included high levels of identification, empathy, responsibility, and the third factor.

During especially challenging times Maria’s development dropped to the third level of positive disintegration. She was mostly governed by level III dynamisms such as dissatisfaction with oneself, inferiority toward oneself, and positive maladjustment. Even during this difficult period, however, Maria’s behaviour demonstrated dynamisms from higher levels of development such as autonomy, responsibility, and empathy. This observation is in keeping with Dabrowski’s statement that “in the process of development the structure of two or even three contiguous levels may exist side by side.” After emerging from a dark period, Maria’s development bounced back to the fourth level of positive disintegration and her behaviour was guided by subject-object in oneself and the third factor.