For the length of this composition, I invite you to conceive of me, the writer, as a dodo.

And not just any kind of humdrum, everyday dodo, but a dodo of taste and leisure, versed in the fine arts and carefully tuned to all the delicate wavelengths of culture. Yes—you see it now? My avian form, cuddled in an elegant armchair on a stormy night, beside the raging fire, as the strains of a distant violin whisper into the spaciousness of my chambers.

Naturally, I am reading. And, just as naturally, I invite you to join me in my perusal of the written word for a moment. I am nosing through a poem of Theocritus, lost poet of an ancient era, in the Greek original. The eleventh idyll, to be specific—the one about the cyclops. Please, pull up a chair. Let me help you. Brandy? Good. So, as I walk you through these echoing lines, I ask you to bear my dodo-hood partially in mind, at the rear of your consciousness, as the fact that I am a dodo has something to do with the ultimate thesis of this piece.

A Long Line of Birds

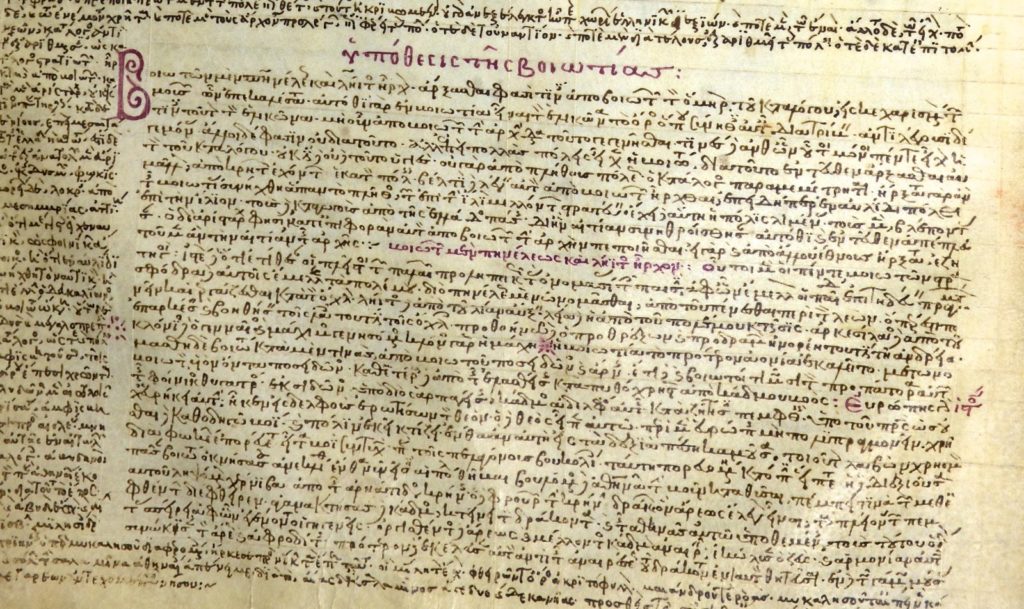

The book is open on my knee now, and all we see are pages of smiling Greek. It is so beautiful, isn’t it? And we aren’t the first at all to read it, no no no… For Theocritus, who lived in the third century BC, always has been a difficult and engaging poet, and he has attracted migrations of the feathered intelligentsia to his side since antiquity. First there were the ancient scholiasts whose marginal notes to help the reader were later anonymously divided into three flocks, all with their own plumage: the Ambrosian, the Vatican, and the Laurentian—named for the libraries in which they were found, you know. Such blessed, learned fowl they were!

Used under a CC Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License

Another flight of commentators shot by in the Byzantine era, including the loquacious, ebullient Tzetzes (strange bird if ever there was one), and the eminent magister Maximus Planudes, from whose very quill dripped with the liquor of poetry. Theocritus’ idylls appear in type for the very first time in 1480 in Milan, and by 1566 the learned Stephanus has had a chance to scratch at the corpus, arranging the verses into their current order with his gleaming claw. Flapping on into the 19th century, we find an intellectual titan with an utter ostrich of a name – say it with me now:

Enno Friedrich Wichard Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff

who squawks out a critical edition of the text, which was later hatched by A. S. F. Gow in 1950 as the version of the work we will read today.

Why mention this? For the companionship. By giving this odd, Doric author our time, by bending an ear to the antique page, we participate in the noble effort to unlock the fragrant casket of the past. When we read the words Wilamowitz touched, we breathe his air, and when we puzzle over the obscure glosses to a twisted form of speech, whispered by the adherents of a religion long dead in a remote land, we keep them alive for the next generation.

The Passions of the Cyclops

Of course, before we begin, I should make a brief note about the language: this is a Doric poem, written in the Syracusan variant of dialect spoken in and around Sparta. So it is a Greek poem written in an Italian form of the tongue, by a resident of Egyptian Alexandria. What does this mean? It means the forms are strange and difficult: it is like reading a cubist painting, in which we find an ear here, a nose over there, an eye somewhere else nearby, but fail to really recognize a face. But this is part of what makes it fun, isn’t it? I assure you, it is.

The Cyclops, Polyphemus, in Theocritus’ poem is not the bellowing, man-eating brute he once was in the Odyssey: here, he is transformed into an emo waif-child, pierced through with longing for his unattainable beloved, and unable to even raise a full beard. After a brief dialogue between the poet himself and a friend on an amorous topic, the scene opens on the poor, monocular wonder, bawling his eye out at the seaside. He is in love with the sea-nymph Galatea, and he croons to the waves of his pain.

But, in his hopeless plea for her attention, it becomes obvious that he doesn’t get around much: the only things he knows how to liken her to are barnyard animals and objects, like grapes and sheep. This fact becomes even more apparent when he drifts from despondent whingeing into nagging pleas for attention. He promises that, if she were to return to him, he would provide her with loads of cheese in a highly reliable fashion—I’m not joking! It says τυρὸς δ᾽ οὐ λείπει μ᾽ οὔτ᾽ ἐν θέρει οὔτ᾽ ἐν ὀπώρᾳ, / οὐ χειμῶνος ἄκρω, check for yourself!—and that he has the young of various animals strewn about, which will more than make up for his snub nose, weird, over-hanging brow, and (let’s be serious) single, staring eyeball. Then after some further mewling, he changes course and declares that it would be a very nice thing if he was just covered with fins so he could go down there, beneath the waves, and be with her himself. That would solve everything. When this also fails to elicit a response or do anything to help him at all, he throws up his hands and blames the whole thing on his mother, Thoosa, who is also a sea nymph, and is probably bad-mouthing him to her behind his back, non-stop. Yes, that’s it! Mom’s the problem. In a huff, he decides that there are perhaps other ladies out there, and besides he’s got a ewe that needs milking. And that’s basically it; the poem ends there.

Strange, isn’t it? A poem about a semi-comprehensible adolescent with no depth perception managed to last more than two millennia, and we just read it today. But isn’t it kind of sad? Imagine it. A young man, aware of his ugliness, howling on the wave-beaten shore, desperately trying to characterize a beauty that he knows he will never hold, and which he can describe in only the rudest, most rustic terms. And even were he, somehow, to win her over, she is a creature of the water, he the land; how could they ever be together? And yet again, even in this, there is a cruel twist in poor Polyphemus’ past: his mother was a sea nymph, as we have said, but his father was Poseidon, Lord of the Ocean, and there is no reason he should not expect to be able to frolic among the waves and sport with the shimmering fishes.

Polyphemus’ mother was a sea nymph, but his father was Poseidon, and there is no reason he should not expect to be able to frolic among the waves and sport with the shimmering fishes.

In essence, he is a bird born without wings…perhaps a little like me. I have wings, it’s true, but I can’t do much with them.

And the Dodo, Revealed

Now we come to me, and my being a dodo. You see, this essay was really about the experience of intellectual isolation, and the emotional trajectory of life without a companion to share the little experiences of the mind. I hid that from you, at first, because I didn’t think it would be appropriate to strike out on that note at the beginning. People tend to prefer cigars and apertifs to discoursing on the experience of a mind marooned. And I liked the poem, if I’m being honest, as lonely as reading it made me feel.

I should note that David Quammen, in a book about my kind, made an important point: extinction occurs before the death of the final representative of the species. He asserts that a line of life becomes unrecoverable at the point where the few remaining individuals can no longer find each other, or the hope of a new generation is otherwise lost, whatever the reason. And when I look at that lineage—all those names I mentioned earlier on—I feel this very keenly. There were sires and grandsires who came before me, mated, cared for the clutch as it rose, and went on their final migrations with the assuring comfort that another flight would rise up behind them, in time. Some of those birds were even quite eminent: Hugo Grotius, the founding mind of international law and original propounder of the freedom of the seas in the 17th century, translated Theocritus and marveled at the poet. Not now.

A line of life becomes unrecoverable at the point where the few remaining individuals can no longer find each other.

O, Galatea…

But why does it have to be so? Why are others not drawn to these little things, that are so pleasurable, and so innocent? I know that you are out there, if only we could find each other. It is so easy to imagine oneself, strutting on the shore in the rhythm of the surf and tide, calling out. I am here. Who are you? Where are you? I would lay out the whole riches of my store to draw you in! But it is like enticing the wave with cheese and sheep: mutely blue and hopeless to the core. And it’s not as if there is not life on the island: it teems with crabs and lizards and an abundance of small mammals…but not another dodo to be found. And yet, somehow, there seem to be so very many dodos today, one on every islet, and all facing their private extinctions just the same. It is so strange.

Why are others not drawn to these little things, that are so pleasurable, and so innocent? I know that you are out there, if only we could find each other.

And that’s enough of that. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have something else I’d like to be looking at, and weather’s gotten cold. If you’ll just draw the door closed behind yourself, I’ll try to keep quiet, and you won’t even know that I’m here, after a while.